What can we learn from the failure of the Alinari company?

Translations

- Come i nostri cellulari ci sottopongono alla sorveglianza continua

[Italian] Preso d'assalto il Campidoglio: le app li hanno rintracciati.

Due giornalisti sono riusciti a identificare non solo molti assalitori del Campidoglio americano, ma anche chiunque era nei paraggi, grazie ai dati, niente affatto anonimi, trasmessi in automatico dai loro telefonini. Siamo tutti pedinati.16 February 2021 - Charlie Warzel & Stuart A. Thompson

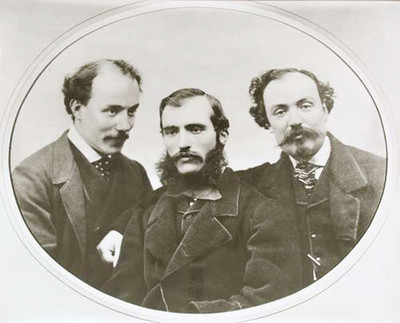

The Alinari Archives is one of the most important photographic archives in the world. Its history began in Florence in 1852 when the brothers Leopoldo, Giuseppe and Romualdo Alinari opened their photographic laboratory. Over the decades, the farsight and passion of the Alinari brothers succeeded in building a patrimony of inestimable historical value for the capacity of the photographs to document the variety of the Italian cultural heritage and, at the same time, customs and traditions of a society in rapid transformation between the 19th and 20th centuries.

The archives, which contains more than 5 million photographic documents including positives and negatives, frames, optical instruments and other photographic-related material, recently risked to be dismembered because of the bankruptcy of the Fratelli Alinari I.D.E.A. company. In fact, in this circumstance, the owners of the archives were forced to sell the building in Largo Alinari in Florence, historical headquarter of the company, as well as the archives itself which, at the beginning of 2020, was acquired by the Region of Tuscany, which established the Alinari Foundation for Photography (FAF) to ensure the management of the huge Alinari patrimony.

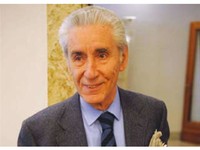

The challenge has been taken up by the new President of the Foundation, Giorgio Van Straten, who, in a recent interview published in the Giornale dell’Arte, indicated the future guidelines for the management of the Foundation. According to Van Straten’s point of view, the economic exploitation of the digital reproductions of the photographs on the web will represent one of the strategic assets of the new management, in close continuity with the previous approach, in the conviction that in this way it will be able to produce incomes that will be useful to cover the foundation’s expenses (above all from the time when it will no longer receive direct funding from the Region). In this regard, the President Van Straten said that “whoever uses the images for promotional, advertising and editorial purposes” “must contribute to the costs of the foundation”.

A vision that seems limited, if we consider the failure of the Fratelli Alinari I.D.E.A. company as another testimony of the fragility of business models based on the e-commerce of images. In fact, the company was able to produce profits selling photos in the analogue era, in which the realization of such products had high production costs and they were not easy to reproduce and replicate. In the present context, however, the wide circulation and reproducibility of digital images through the web makes such a model out of date, as some of the world’s major Cultural Institutions have realized in the last ten years.

The extraordinary photographic collections of the New York Library have been digitized and published on the web at very high resolution so that anyone in the world can freely reuse it for any purpose (even commercial). Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam makes available reproductions of its collection in high resolution under CC0 license; in Italy, the Egyptian Museum Foundation in Turin, as in the case of Alinari, manage digitized public cultural heritage released under CC BY 2.0 license. These cases prove that the free reuse of images, far from determining an economic damage for the institutions, allows a relevant economic saving on the costs of administrative management practices, igniting the interest of the public on the cultural heritage and contributing to generate economies much more important than those originating from the sale of the images. While free reuse seems to have become a fundamental part of the mission of Cultural Institutions in the digital age, the Alinari Foundation doesn’t want to change the approach of the past, underestimating the potential of the digital technologies as a lever of development and innovation. In fact, the current epidemiological emergency emphasized the difference between the physical cultural heritage, whose use is always exclusive, and the digitized cultural heritage, which can be used by anyone at the same time, contributing to the dissemination of knowledge and stimulating publishing and every form of creativity.

Moreover, the Foundation’s strategy appears even more anachronistic if we consider the imminent reception of the DSM Directive 2019/790/EU by Italy: in fact, art. 14 of the Directive requires Member States to remove related rights on faithful reproductions of works of visual art in the public domain, in order to promote the free reuse of the reproductions themselves, even more if they reproduce public cultural heritage.

Historical memory is important not only to learn from the past, but also to reflect with greater awareness on the present. In this sense, it is important to consider an episode of the past: on March 25th, 1892, Vittorio Alinari wrote from Florence to the Minister of Education asking to reject a proposal for a law that imposed fees on photographs of works of art for commercial purposes (a proposal that became reality with the Nasi Law of 1902 and is maintained by the current Code of Cultural Heritage). Now that the Alinari patrimony is in the hands of a public body like the Region of Tuscany, it comes as a surprise that the Foundation defends the same fees that Alinari, in the past, asked to be removed in order to promote the art of photography.

Finally, it is legitimate to think about another aspect that seems secondary but which could have further repercussions on the management of Alinari Foundation’s e-commerce: the possible interference with the Italian Cultural Heritage Code (D. Lgs. 22/01/2004 n° 42) that anachronistically limit the free use of images of public cultural heritage (such as the Alinari photographs) excluding the commercial use. If it is true – as seems evident – that there will be no discontinuity with the previous business management in terms of licensing, how will the Foundation manage the cases in which the photographs contain public monuments? The fee for the commercial use of the public cultural heritage (stated by art. 108 of the Italian Cultural heritage Code, that are contained in the photographs, will be added to the fee for the commercial use of the Alinari photographs themselves? Is there already any kind of agreement in this sense with the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage?

It seems that the Foundation has missed an extraordinary opportunity to become a positive example for diffusion, in Italy, of the Open Access values, that represent the best interpretation of the role of public service. The origin of the Alinari archives as a private company, aimed solely at profit, still seems to have an important weight in the strategic choices of the new Foundation. Therefore, we wish the new President Van Straten the best in managing and promoting the patrimony of the Alinari archives, rethinking the policy of images management and encouraging the sharing and effective use by the community, as the primary purpose of the public activity regarding the cultural heritage. So, we hope that the watermarks will give way to high-resolution images and the rigid and traditional system of fees for commercial uses will be replaced by the free reuse of the digitizations of Alinari photographs, accordingly with what Creative Commons, Europeana, Wikimedia, Communia and the OpenGlam community all over the world have been asking for long time.

Articoli correlati

Intelligenza artificiale e pace - Criticità e opportunità

Appunti per attivisti pacifisti allo scopo di orientarsi nel nuovo mondo dell'intelligenza artificiale7 gennaio 2024 - Francesco Iannuzzelli Se il mondo perde il senso del bene comune

Se il mondo perde il senso del bene comuneLa tecnologia apre le porte, il capitale le chiude

Vi è oggi la necessità di contrastare la sottrazione alle persone delle opportunità offerte dall'innovazione scientifica e tecnologica. Internet rischia di trasformarsi da risorsa illimitata in risorsa scarsa, con chiusure progressive, consentendo l'accesso solo a chi è disposto ed è in condizione di pagare. Oggi i beni comuni - dall'acqua all'aria, alla conoscenza, ai patrimoni culturali e ambientali - sono al centro di un conflitto planetario.24 agosto 2010 - Stefano Rodotà Tesi del Master "Scienza Tecnologia e Innovazione"

Tesi del Master "Scienza Tecnologia e Innovazione"Dal pensiero strade per innovare

Software e comunicazione digitale, circolazione della conoscenza ed esigenze di tutela della proprietà intellettuale28 gennaio 2010 - Lidia GiannottiCreative Commons, una rivoluzione lunga 5 anni

Il 16 dicembre 2002 facevano il loro esordio le licenze alternative ideate da Lawrence Lessig. Iniziava una nuova fase nella gestione della creatività e dei diritti d'autore nell'era digitale. Parla Juan Carlos De Martin13 dicembre 2007 - Marco Trotta

Sociale.network